From Lagos to Dakar, conversations abound about the future of work and how innovation continues to disrupt what we think we know. New technologies like artificial intelligence and robotics still generate understandable uncertainty about what roles humans will be able to play in the labour force in another five years. Countries with very little investments in developing human capacity in science and technology, will not fare well with this rapid flux.

“I predict that there will not be a shortage of jobs in the future, but rather a shortage of skills to fill the jobs,” writes Stephane Kasriel, CEO of freelancing platform Upwork.

In fields like science, technology, engineering and mathematics, this shortage of skills in Africa is not only a result of infrastructural deficiencies, lack of foresight in policy development or refusal to discard outdated learning curricula and create new ones that meet the skill demands of the future, but also cultural shortcomings that limit learning possibilities and involvement of women in this rapidly evolving sector. To compensate for this lack of appropriate school curricula and other such shortcomings, initiatives abound across Africa, training girls in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, and helping them develop applied and problem-solving skills that are required for careers in the future. But these come at a cost.

“A program training cycle begins long before the program is conducted and continues after it has been completed. It starts from the planning stage and ends at the evaluation stage,” says Adeola Shanaya, co-founder Afro-Tech Girls.

Founded in 2014 with Morenike Johnson and Yvonne ‘Nkem’ Allanah, Afro-Tech Girls is one of a number of initiatives in Lagos looking to bridge the gender gap in STEM fields in Nigeria by offering training and mentorship to young girls.

Students participating in the maiden edition of the Afro-Tech Girls Sciletes (pronounced sai-leets) Quiz Competition in 2015

Source: Afro-Tech Girls

The planning stage, an intense number of weeks and months leading up to any training cycle, involves assessing and analysing what topics or skills to be taught, developing learning objectives and designing the actual program including deciding on the number of participants the program can take at the time, content of the training, program venue, facilitators and publicity, among other things.

“Finally we have the evaluation stage which entails feedback from participants/trainers. It tells you if objectives were accomplished and we also use this feedback to improve future programs,” adds Adeola.

Tech Needs Girls is a training scheme organised by Soronko Academy, a Ghanaian initiative founded by software engineer, Regina Honu, in 2013. With 4,500 alumni, the initiative runs coding trainings alongside courses in entrepreneurship and acquiring digital skills for business.

But this is no easy task especially with the negligible budget allocations for education in general, in Africa. According to UNESCO Institute for Statistics, countries in sub-Saharan Africa spend, on average, just 0.5% of their gross domestic product (GDP) on science, research and development. In 2018, Nigeria’s federal government budgeted only 7.04% of the annual budget on education, far below the 26% of national budget recommended by the United Nations. This was only an very slight improvement from the 6% of the previous year. In 2010, 2012 and 2017, World Bank reports say Senegal spent 6.5%, 5.9% and 6.2% of its GDP on education, all significantly below the recommended benchmark of the United Nations.

“One training cycle which runs for 6 weeks for a minimum of 25 people costs about $5,000 -$8,000 not including the costs of purchasing the equipment. When equipment costs come in you are looking at about $15,000 for 25 people in addition to the running cost which is $5,000 -$8,000,” says Honu. “These are the costs when you run your own facility in certain areas.”

Girls in training at a Soronko Academy Tech Needs Girls program

Source: Soronko Academy

Honu says to cut costs, the team sometimes has to seek the support of the communities where the training programs are held to provide things like a venue.

In spite of high running costs, course fees at the academy range from GH500 to GH700, roughly US$96-US$135. Income from course fees at the uppermost range totals US$3,375 for a class of 25, which is not enough to cover the capital expenditure on each training session let alone turn out profit.

JjigueneTech Hub in Senegal is one STEM initiative with its own facility–a five-room office located in the capital city of Dakar. Trainings offered at the hub range from an introduction to basic IT skills, such as the use of programmes like Microsoft Word and Outlook, to computer coding with languages such as HTML and CSS. All trainings are offered free-of-charge at JjigueneTech, which gets its name from the Wolof word for female.

According to this BBC report, sponsorship from local businesses and Microsoft, which has an office in Dakar, makes this possible.

“The cost of running a training cycle is dependent on the training type. A lot of factors have to be considered and it varies with each program. The cost of securing a venue alone can start from N50,000 (US$139) for one day,” Adeola says, and one has to consider venues with computing equipment that are key to these trainings.

Except when a training session is paid for by participants, Afro-Tech Girls funds its cycles through grants, sponsors, and support from friends and family.

“We source for training materials ourselves from the facilitators or trainers.”

Thanks to social media, disseminating calls for applications is a lot easier but for Afro-Tech Girls, some paid publicity doesn’t hurt.

“For crafting messages, we basically put what the event is about, why it’s important and the age range. I think it’s more of the enthusiasm from the girls and willingness to learn that gets them to apply,” Shasanya says.

Organisations like Paradigm Initiative, a digital inclusion initiative based in Lagos, Nigeria, are of the opinion that language and messaging around application calls for STEM training goes a long way in encouraging girls to apply. With just enough tutors and volunteers, both initiatives are able to cater to the applicants it receives every training cycle. Finding credible STEM tutors, however, can be a challenge.

“We partner with reputable organisations so they provide facilitators for most of our programs while some are professionals within our network or referred,” Shasanya says, but timing and prior commitments on the part of the tutors can become a stressful situation to deal with.

At Soronko Academy, the challenge presents itself more uniquely.

“Some trainers are good at the technical aspect but cannot teach. Some do not have prior experience with teaching and some also find it hard to simplify the coding to the understanding of the girls,” says Honu.

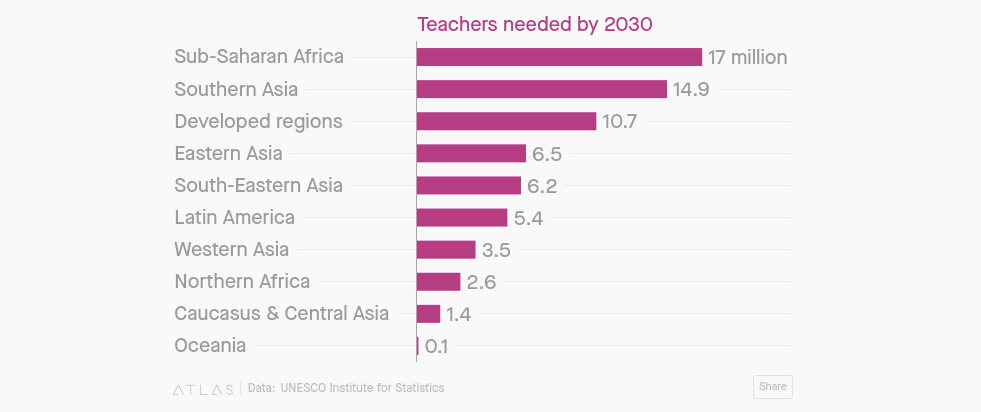

Understandably, UNESCO Institute of Statistics released a report in 2016 showing that to meet its 2030 Sustainable Development Goal of universal primary and secondary education, sub-Saharan Africa requires 17 million more teachers than it already has.

Sub-Saharan Africa needs 17 million more teachers by 2030

Source: Quartz

STEM education, nonetheless needs to move beyond coding and software development classes to embracing the full spectrum of what the acronym denotes. What this field of learning offers goes beyond learning to write lines of code to developing critical thinking and problem-solving skills that are required to thrive in the future.

“We have a curriculum that is developed with local context, very interactive and practical. We believe technology should come to life for the girls and they should be able to see how what they are learning can be used to solve problems around them,” says Regina Honu.

Courses at the academy include web and mobile app development as well as soft skills such as leadership, public speaking, negotiation, entrepreneurship and presentation skills.

“We want to develop confident girls who are tech-savvy problem solvers.”

Afro-Tech Girls also offers an interesting curriculum, from the basics of computing to 2D animation, and summer camps on renewable energy and robotics.

A report published in 2009 by the International Youth Foundation says that in Senegal women hold 35% of the IT jobs in the country. Nigeria’s National Bureau of Statistics says that boys are twice as likely to have careers in science and technology-related fields as girls and on average, just 22% of the total number of engineering and technology university graduates each year are women. Statistics compiled by UNESCO reveal that, globally, women make up less than 30% of people working in STEM careers and the numbers are lesser in a number of countries in sub-Saharan Africa. But bridging this gap will come at a cost and both government and private partnerships working together on issues like funding, developing academic curriculum that are in tune with the demands of the future and contributing to growing the numbers and quality of teachers in this field, will go a long way in making an impact that will be felt across the continent.

PS: We published a list of initiatives working to get more girls and women into STEM fields. Here’s the list and a form to fill to help us populate this list even further.

The post The Costs of Securing Africa’s Future Through STEM Education appeared first on TechCabal.